The embarrassing era of “Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Boxing” will continue Saturday night with perhaps its most offensive event to date.

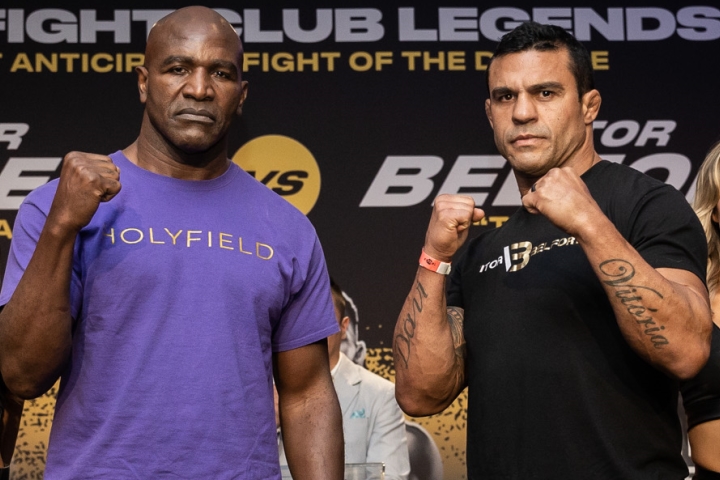

How else are we supposed to view a farcical fight in which a 58-year-old former heavyweight champion will end a 10-year retirement to box a mixed martial artist who is 14 years younger, yet far less experienced in this sport? Former UFC light heavyweight champ Vitor Belfort was supposed to box another long-retired, 48-year-old legend in what was a questionable bout, too, but Oscar De La Hoya contracted COVID-19 and withdrew from their cruiserweight contest last week.

The fact that Holyfield-Belfort, like De La Hoya-Belfort, has been sanctioned for eight two-minute rounds, rather than the standard three-minute rounds, is a clear indication that they shouldn’t have been licensed for an official fight. An exhibition would warrant skepticism as well, but at least then they could take liberties with the terms of competition, like Mike Tyson and Roy Jones were supposed to do last November 28 at Staples Center in Los Angeles.

It would be best, obviously, if Holyfield, despite his impressive physique, could simply enjoy being an iconic ex-champion as he nears senior citizenship. Instead, the four-time heavyweight title-holder has become an exploited legend who will attempt something inherently dangerous for 28-year-olds, let alone men more than twice that age.

Bob Arum is among the sport’s powerbrokers who have taken issue with Holyfield’s return to the ring.

“When you’re at a certain age, you have to give them a more extensive physical than you do regular fighters,” Arum told BoxingScene.com. “They gave Holyfield no physical at all when they approved him. That’s nuts. That’s totally against why we have commissions or anything.”

The Florida Athletic Commission has medically cleared Holyfield to battle Belfort in the main event of a Triller Fight Club Pay-Per-View show at Seminole Hard Rock Hotel & Casino in Hollywood, Florida (7 p.m. EDT; $49.99). The entire event was moved from Staples Center in Los Angeles to South Florida primarily because the California State Athletic Commission understandably would not grant Holyfield a license.

The CSAC approved Tyson-Jones, but only as an eight-round exhibition. Tyson, then 54, and Jones, then 51, were closer in age than Holyfield and Belfort as well.

Regardless, what exactly is the point of this Holyfield-Belfort bout? Unlike Holyfield and Tyson, whose third fight probably shouldn’t happen, either, they have no history whatsoever.

If Holyfield wins, he’ll have beaten a retired MMA fighter who went 2-4 in his last six MMA matches. If Belfort beats Holyfield, how much credit would he deserve for defeating a faded former champion who’s pushing 60 and hadn’t fought in 10 years?

As alarming as this Holyfield-Belfort fight might be, it isn’t the only objectionable bout on boxing’s schedule this weekend. For those who worry about this sport’s safety standards, from either enjoyment or professional perspectives, the Oscar Valdez-Robson Conceicao controversy is troublesome, too.

Valdez tested positive last month for Phentermine, a stimulant banned by the Voluntary Anti-Doping Association both in and out of competition. VADA oversees the WBC’s “Clean Boxing Program,” in which that sanctioning organization requires all of its champions and contenders to enroll.

Mexico’s Valdez received a license from the Pascua Yaqui Tribe Athletic Commission because, like all state and tribal commissions in the United States, it adheres to the World Anti-Doping Agency’s guidelines for performance-enhancing drugs. WADA’s regulations permit Phentermine use “out of competition,” as long as it isn’t detected after 11:59 p.m. local time the day before an event.

The 30-year-old Valdez claims he doesn’t know how Phentermine entered his system. The WBC super featherweight champion also acknowledged that he realizes he is responsible for whatever is ingested in his body.

Arum and Patrick English, an attorney who represented Valdez in this matter, think drinking an herbal tea during training camp triggered Valdez’s positive test.

Arum, English and WBC president Mauricio Sulaiman have defended Valdez’s character and admirable behavior both in and out of the ring. While Valdez has previously embodied everything that’s right about boxing, that doesn’t change the fact that he tested positive for a substance banned by VADA, even if it wasn’t intentional.

Phentermine, primarily used to lose weight, isn’t comparable to an anabolic steroid, but Valdez essentially escaped this mess without suffering any real consequences. That’s unless you count the WBC placing Valdez on probation, whatever that means.

Some sort of suspension and a postponement of the Conceicao contest seems more appropriate.

Mired in a comparable predicament, the Massachusetts State Athletic Commission refused to license Billy Joe Saunders for a WBO middleweight title defense against Demetrius Andrade in October 2018 in Boston. England’s Saunders tested positive for oxilofrine, which Saunders contended came from using a nasal spray.

Oxilofrine was on VADA’s list of banned substances. WADA allowed it “out of competition,” but the Massachusetts State Athletic Commission still denied Saunders’ application for a license.

The Pascua Yaqui Tribe Athletic Commission should’ve taken the same approach to the Valdez ordeal. At the very least, the WBC should’ve refused to sanction Valdez-Conceicao as a title fight Friday night at Casino Del Sol in Tucson, Arizona.

Otherwise, what’s the point of VADA testing its champions and contenders? Sulaiman offered a long-winded, unconvincing explanation for the organization ignoring VADA’s findings and condescendingly chastised anyone with the perceived audacity to criticize an obviously questionable decision.

Of course, if this ESPN+ main event would’ve been downgraded to a non-title fight, the WBC would not be “entitled” to its typical three-percent cut from the purses of Valdez and Conceicao.

Arum claims this Valdez debacle will lead to the WBC altering its “Clean Boxing Program.”

“The WBC realized, I believe, that they were out of step,” Arum said. “VADA is a great organization to report substances and so forth. But they are not an adjudicating body. What the WBC has to do is adopt WADA, like every other serious organization in sports has done. Football, basketball, soccer, track and field, all of them, they follow WADA. And you don’t denigrate VADA because they just report.”

What’s indisputable is that this sport still poorly polices performance-enhancing drugs, in large part because there isn’t a particular party responsible for funding expensive, comprehensive testing throughout training camps for every licensed professional boxer. Beyond PED use, this weekend’s wackiness in Florida has drawn more attention to the need for more responsible safety standards in boxing.

“When you’re at a certain age, you have to give them a more extensive physical than you do regular fighters,” Arum said. “They gave Holyfield no physical at all when they approved him. That’s nuts. That’s totally against why we have commissions or anything. I mean, maybe Holyfield is a specimen that we’ve never seen before, but I don’t believe that. I mean, we know how many punches he took. Maybe one more punch, you know, will put him on queer street. We don’t know that. I mean, what kind of people are we?”

With what’s been allowed in boxing this weekend, there might not be a more appropriate time to ask that question than now.

Credit: Keith Idec / Boxingscene.com