Like most of Africa’s celebrated sportsmen/women, Kenya’s star boxer Philip Waruinge died without any substantial reward from the Kenya government or well wishers to show for his illustrious career in the ring.

Yet other countries honour their sportsmen/women with lavish gifts and monetary rewards for their achievements.

For instance, Botswana’s 4x100m relay quartet was rewarded with a two-bedroomed house each for winning a bronze medal at the Tokyo Olympics.

For Ghana’s Prince Amartey, it was a case of better late than ever.

A middleweight bronze medallist in the 1972 Munich Olympics, Amartey had to wait for 49 years to be honoured by his former employer, Ghana Armed Forces who gave him a fully-stocked shop at the age of 77 when he was ailing and on a wheelchair.

This happened following a petition by the family to the Chief of Defence Staff to come to the rescue of the former soldier who was then going through hard times coupled with health challenges.

The belated move elicited mixed reaction from Ghanaians with some hailing the generosity of the Armed Forces and others terming it a big joke to reward an ailing 77-year-old with a shop, wondering how he would handle the new venture. Waruinge was also a soldier with the Kenya Defence Force (KDF).

Now contrast the aforementioned with the millions of dollars showered on Jamaican athletes for their success at the Tokyo Olympics.

A total of $41 million was at stake for the athletes and some coaches in an investment trilogy between the Jamaican Olympic Committee, Supreme Ventures Limited and Mayberry Investments.

Gold medallists were to receive $6 million dollars which is Ksh 728,000,000, silver $4m and bronze medallists $2m.

In the current reward scheme for Kenyan medallists, gold medal winners receive Ksh 1,000,000, silver 750,000 and 500,000 for bronze medallists.

For the great Phillip Waruinge, there were no monetary rewards during his time in the ring. They were doing it for the love of the country.

That’s why he decided to belatedly turn pro at 28 years in 1973 after winning a silver medal at the 1972 Munich Olympics. His mission was of course to make money and empower his family financially.

He was not as successful as he was in amateur boxing, retiring with a record of 14 wins, 10 losses and one draw.

On stepping out of the ring, Waruinge ventured into coaching and business in Japan, exporting electronics to the USA, Kenya and South Korea. He also operated Champions Snack Bar which was doing well and the future looked bright for the stylish Kenyan boxer.

But his world turned upside down in 2007 when he was deported for failure to renew his visa.

“In Japan this is a serious offence,” he told me taking into account this was the second time he had defaulted.

“When I failed to renew my visa for the first time l apologised and told them l would not repeat the same mistake.”

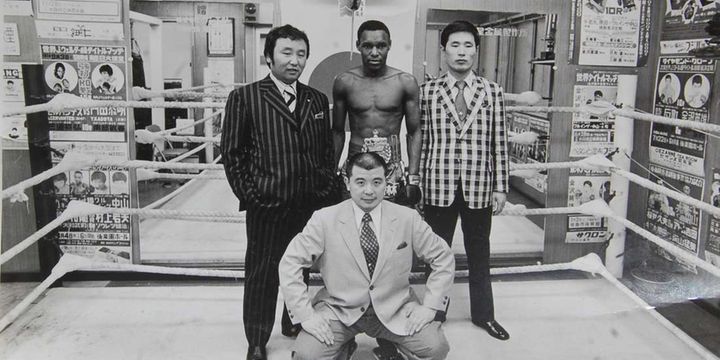

Photo credit: Francis Mureithi | Nation Media Group

This time around he was taken to court and from there to the airport.

“I just travelled back home with the clothes l had on, nothing else. Even my medals l left them behind in Japan and my bar business.”

Life for Waruinge since returning home had not been a bed of roses financially. Apart from his loving family and a few close friends, Waruinge was a lonely warhorse, spending some of his free time in the library in Nakuru town. He was a voracious reader.

In a capsule summary, he was neglected and unrecognised at home.

“It’s sad my close friend and clubmate at Nakuru ABC, Waruinge died a poor man with all Kenyans watching,” says Philip Mainge, one of the pioneer boxers of Nakuru Amateur Boxing Club. The gym is popularly known as Madison Square Garden.

Even subsequent regimes of boxing federation officials had no time for him despite his wealth of knowledge which he would have shared with upcoming boxers but that, it seems, was not important to the boxing barons.

The boxing officials never initiated any significant move with the government or the private sector to appreciate and reward Waruinge for his sterling performance for Kenya.

Boxingwise, the gifted boxer had his own unique way of sharing his wealth of boxing knowledge.

Fortunately enough I gained a lot from him on the art of boxing in the several interviews I did with Waruinge whenever I visited Nakuru, now nicknamed NaxVegas from Rukuna in the 80s.

Waruinge was a humble man and down to earth. Hardly would you notice his presence in the streets of Nakuru. He mostly kept to himself and preferred not to be a burden to anybody. He protected his dignity zealously despite his limited resources.

Kenyans may have deserted Waruinge in his hour of need but his children and a few reliable friends were always there for him. His children and wife Mary have been very supportive during the hard times he went through especially his last born son Tom who is based in Japan.

“I wish I had turned pro early enough I would have made a lot of money but I lacked good advisers in Kenya, mostly they were keen to see me winning medals for the national team.

“Unfortunately I’ve not seen the value of all the medals I brought the country,” he would always tell me in the interviews I had with him but he was not bitter secure in the knowledge he had played his part.

“I will not force them to reward me. They know what I’ve achieved so the ball is in their court. Personally I’m happy for what I achieved,” said the quietly spoken Waruinge whose younger brother Sammy Mbogwa, a retired senior Prisons officer, was also an accomplished international boxer.

As Kenya’s sports fraternity mourn the 1968 and 1972 Olympics bronze and silver medallist, there’s been nothing official from the Kenya government to console the bereaved family of the fallen hero who’ll be laid to rest next Friday.

Credit: Nenez Media Services