The beauty is when the ball takes flight. Once it leaves his fingertips – always rolling off the tips with a familiar flick – it begins its spin and all eyes are locked on what looks like perfection.

Stephen Curry has just launched another 3-point shot, and the game of basketball just took another rotative turn along with the Wilson ball that’s about to splash through the hoop.

It happened in the last Golden State Warriors game. And the one before that one, and the one before that one and it’ll no doubt happen in the next game as well, because certain nightly basketball assumptions seem safe, like sweat and fouls and Curry breaking the spirit of poor defenders who instinctively know their fate even before the sound of the swish.

It’s got to the point where there’s no shame in being a victim to the best to ever do it, to someone with a shot dipped in barbecue sauce, to someone who is leaving an everlasting impression on a sport that thought it had seen it all, and yet…

“What he’s doing is revolutionary,” says Doc Rivers, the Philadelphia 76ers coach who has had to game-plan against Curry for a decade. “Only the greats can do that, leave their mark like that. Actually, the great-greats. They change the game.”

George Mikan made the NBA widen the lane. Bob Cousy wrote the manual on the pass. Elgin Baylor showed how to play in the air. Chamberlain changed rules. Larry Bird and Magic Johnson saved the league. Tim Hardaway redefined the crossover dribble. Allen Iverson caused a cultural shift. Dirk Nowitzki defied European stereotypes. Michael Jordan created the marketing machine. The Dream Team welcomed the world to basketball.

Game-changers all. Steph Curry moved the game 23 feet from the rim, and beyond.

game 23 feet from the rim, and beyond.

“You go to AAU games,” said Rivers, “and these kids are jacking up shots from halfcourt.”

That’s not altogether a negative connotation because Rivers is quick to add this:

“Shooting gets better around our league each year. You see that. That’s his impact. That’s what Steph is doing for basketball.”

When it comes to Steph, Ray Allen was helpless, too. Allen couldn’t prevent the inevitable, not while sitting in his retirement rocker. His career 3-point record of 2,973 has now been topped by Curry and, health permitting, Curry will now stretch it beyond recognition. It is about to become one of those unbreakable sporting records if this trend by Curry continues, entering a domain filled with Wilt Chamberlain herculean feats, and once there it will surely collect dust, never to be approached in our lifetimes.

Curry in 2012-13 set the NBA seasonal mark for most 3-pointers with 272, then bested that two years later with 286, then went Uber-level with 402 in 2016. This season, he’s paced for another 400-plus and another record erasure. While calculating his running career total, keep in mind that he made only 55 in the regrettable sprained ankle season of 2011-12 when Curry was spooked by the ailment and couldn’t play a full schedule, and 12 in 2019-20 because of a broken hand.

Curry didn’t invent the 3-pointer but, as the poster child, he’s leading the revolution and supersizing it. He has 38 games of nine made 3s or more – nobody else has 10. Allen played 1,300 career games. It took Curry 789 games.

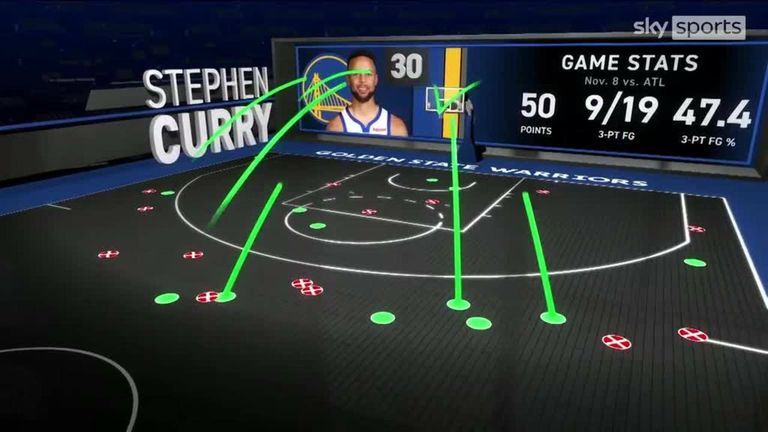

It’s just not the shot that sets Curry apart. It’s the range and accuracy – both are guilty of causing spectators to gasp. He treats 30-footers as others treat floaters, and of course, the signature jumper launched from the logo is a Curry trademark.

More astounding is the efficiency for such a volume shooter; it’s the accomplishment that Curry takes pride in most, because it underscores his talent. The handful of players with higher career percentages than Curry, like Steve Kerr for example, attempted 5,000 or so fewer shots. Curry does not, as the basketball vernacular goes, chuck them up.

When Curry made a 3 for 157 straight games, which is the NBA record, he stumbled and went 0-for-10. The very next game, as if to teach the basketball a lesson, Curry made 13 of 17, his career best.

“He’s on his own level, one he made for himself,” Allen says. “He’s done such a great job. And he has such great character as a person, and you root for people like that. He’s getting everything he deserves.”

Yes, all the flowers. And yet, this mad science required the perfect concoction of a shifting trend, the right genes, pure circumstance and an unquenchable thirst to become a legend. Those are never easy to forecast for anyone, not even a player who was seemingly built for this.

Reasons 1 & 2: His father and the basketball genes and upbringing

Dell Curry, the father who seeded and nurtured this force of basketball, shook his head when asked about his son’s road map to 3-point riches.

“In Chicago the other day, I saw LaVar Ball at the game wearing a hat that said: I Told You So,” said Dell, mentioning the bombastic father of LaMelo and Lonzo.

“Well, my hat would say: I Had No Idea.”

On several occasions after George Karl blew his whistle to signal the end of Bucks’ practice in 1999, a curious phenomenon occurred. Instead of going home, players gathered ’round to witness the show featuring a Holy Trinity of shooters: Allen, who was in the early stages of becoming the most prolific 3-point shooter the NBA ever saw, Dell Curry, winding down a 14-year career as the most accurate distance shooter at the time (47.6 per cent that season) and young Steph, all of 10 years old.

The three teamed up and challenged all comers in shooting contests, usually squaring off against Glenn “Big Dog” Robinson and Vinny Del Negro and whomever else wanted some, and the results were what you’d expect.

“We never lost a game,” Dell says.

Karl, the coach, was so charmed by the kid that he demanded that Dell bring him whenever possible. And Allen? He told the father: “Man, do you know what you have here?”

Not long after he was born in 1988, Steph would attend his father’s games in a portable crib, and Dell noticed how “he woke up when the game started, stayed awake the whole time, then fell back to sleep when it was over.”

And Steph recalls: “When I was 3 or 4, I have faint memories of going to a Hornets game. When I was 6, they beat Boston in the first round in the playoffs and Alonzo (Mourning) hit that jumper from the free-throw line. My father was the inbounds passer on that play. So I have these strong memories of watching basketball. Maybe by osmosis and being around the environment I developed a love for it, developed an understanding of how the game was played. Then I fell in love with shooting while watching my dad. It wasn’t intentional, it was natural.”

So Steph was born into the game, and that’s The Second Reason why he changed it. As for The First Reason? Well, the evidence is decomposed somewhere in a Virginia landfill. That’s where the goal that Jack Curry bought for his son lies. They lived in the Shenandoah Hills, and because Dell had four sisters, there was little for him to do. So he shot on that goal placed on the side of the house by his father – Steph’s grandfather – always mindful of the black bears lurking in the woods nearby, and a legendary basketball link was created.

Dell chuckles at suggestions he’s the Earl Woods of basketball, yet there is some semblance: Earl taught Tiger how to swing a club and Dell taught the greatest shooter how to shoot.

Dell had a rapid release, and that’s where the similarity between father and son starts and ends. Dell was mostly all-wrist – there was very little wind-up in his motion. Also, Dell was a catch-and-shooter. “I had a two-dribble limit,” he says. “Steph creates so much more off the dribble than I did.”

It also helped that for much of his young life, Steph was the shortest player in any group or team. At the time, it seemed like a curse – that’s why the blue-blood basketball programs ignored him and he wound up at a small school called Davidson College – but it forced him to compensate. So he worked on his dribble to create distance between himself and the defender to prevent his shot from being blocked constantly.

The astonishing hand-eye coordination and deceptive bounce are so apparent in his dribble today. Curry owns one of the sport’s most tenacious handles which serves two functions: It keeps the defender off-balance in case Curry decides to attack the basket – that part of his game is so understated – and it also allows Curry to sneakily square up for 3s. Coming into this season, 54 per cent of Curry’s career 3-point attempts had been pull-ups.

“The quick release was more important early,” Steph says. “With my height, I had to use that to my advantage, get my shot off quick. In the NBA, open space continues to get decreased. Then as I got that down, being able to expand my range and create space with the ball, the dribble became equally important.”

Another way to prevent defenders from eating his own shot as a kid: Shoot from deeper distance. And so, again, the development and rise of a game-changer emerged from convenience and out of necessity.

Reason 3: Desire to be the best

“Growing up around the game, going to camps with me, all that played a part,” Dell says. “I also think by being exposed early, he learned how to play the right way. He was always smaller than everyone so he knew he would have to have the guard skills.”

Which brings us to The Third Reason: Steph Curry put in the work, then and now, on fundamentals and skills. It’s the gene in the vein of all the greats. It was “the desire,” said Seth Curry, that set his older brother apart from the pack and continues to do so.

“Even though he’s been the best at it for a long time, he’s still working on his game and improving,” Seth says. “Seems like every year he’s improving his 3-point shooting. He knows everybody’s trying to come up with ways to stop him, so that’s the special part in what he’s doing right now.”

The Steph Curry Practice Experience is unique in its originality, repetition, intensity and relentlessness. There’s a variety of ball-handling drills, followed by shooting from all spots on the floor, and then rinse and repeat, to sharpen muscle memory. He executes trick shots not just for kicks. Curry practices them just in case he feels the need to pull one out of his bag during a game. The process takes hours and it’s done almost daily. His co-pilot is Bruce Fraser, the Warriors assistant coach nationally famous for passing the ball back and forth.

For those left spellbound by the constant clicking of the official Curry 3-point meter, here’s a question: Can you imagine how many undocumented 3-point shots Curry has made, meaning, in a lifetime’s worth of practice?

“I spent time last summer watching him work,” Dell says. “Your average NBA player couldn’t work with Steph. He puts so much pressure on himself in the drills that he does, the shots that he makes, how quickly he gets from one drill to the next. Players try to keep up with him and they can’t. I’ve seen other players work and they do the little things. Steph does things at the fastest and hardest pace. There’s a reason he turned out this way.”

Reason 4: Overcoming physical challenges

The Fourth Reason Why He Changed The Game arrived in 2007 when Curry received his first taste of upper-level basketball. He represented the US in the 19-and-under global tournament and his teammates were from bigger schools and were bigger physically. Among them, curiously, was Patrick Beverley, who later took delight in trying – and mainly failing – to torment Curry in the NBA. There was also Jonny Flynn, who was taken a spot ahead of Curry in the 2009 draft yet had a short NBA career.

“I was guarding Jonny in practice once and he gave me a nice shoulder to the chest,” Curry says. “It stunned me but I took it. So I knew what the physical part was right then. I knew skill-wise I could hang. But physically I was a late bloomer and undersized.”

As he grew older, Curry transformed his body, locating muscles he never knew existed and tightening them without adding much weight, which would steal his quickness. He kept the babyface and just added a man’s frame. That helped him deal with the rigours of games and practice and gain the wrist and forearm strength needed to shoot, not heave, those trademark shots taken from the mid-court logo.

Reason 5: Landing in the Bay Area

The Fifth Reason was a matter of pure luck and timing and a bit of crafty manipulation. Prior to the 2009 Draft, Curry began climbing the charts based on sparkling play in workouts, to the point where he wouldn’t fall to No. 12, where the hometown Hornets waited. The family’s top choice for Curry became the Knicks, selecting eighth, and that, too, seemed tenuous.

Dell Curry went to work, telling the Timberwolves, who had the No. 5 and 6 picks and needed a guard, not to bother. Minnesota took the bait and grabbed Flynn and Ricky Rubio, which amounted to basketball malpractice.

The Warriors grabbed Curry at seven, one spot ahead of the preferred Knicks, leaving the family with mixed feelings. Golden State offered a surplus of playing time and, a few years later, the perfect practice partner and tag-teamer arrived in Klay Thompson (who owns the record for most 3s in an NBA game). At the time, the Warriors were desperate to escape a dark decade. That said, would Curry be Curry had he ended up in Sacramento or Minnesota or even New York where those organisations, either out of bad karma or bad management, endured constant changeover and lengthy dry spells before and since?

Just by chance, the game itself turned breezy and gravitated from the big man and opened the door for a pioneer to walk in and change it. Once Curry overcame persistent ankle sprains, his shot-making gained traction and basketball would never be the same.

Or, as some might suggest: Curry ruined the game by making shooting look so easy – especially shots from deep – that it has poisoned a generation of dreamers with 3-point fetishes and also warped the thinking of general managers and the philosophies of coaches who suddenly hail the 3-pointer above all else. Seven-footers are now spacing the floor and setting up shop beyond the 3-point stripe, nudged in that direction unintentionally by Curry.

“I take it as a compliment, and it’s flattering,” Curry says, “because you stretch the imagination and it’s really hard to influence the highest level. But it’s really hard for coaches and parents and anyone who’s grooming the next generation of talent to understand how much work went into this.

“The curse of society today is everyone sees the finished product but nobody understands how you got there, what the road map was, the amount of reps it takes to get to that level. It’s impossible to see what I do, see the way Dame (Lillard) plays, Trae Young, guys who have similar tendencies, and know what it takes. You just can’t wake up one day and say, ‘I want to go shoot way out here.’ There’s a slow build to get to that level.”

How much further can he go?

The league-wide 3-point growth and trend was apparent before Curry arrived, but by every metric and reasoning, he accelerated it. And when his success in shooting translated into championships, the influence caught hold, not only in the NBA, but trickled down to biddy-ball where kids dreamed of being the next Steph. Those who harbour futures in the NBA believe, with some justification, that they must shoot 3s to even have a chance.

Sticking on the NBA level: Using the 2012-13 season as a launching point only because that’s when Curry finally overcame his ankle yips – and also when he made 11 of 13 in a game against the Knicks – the 3-pointer started devouring growth pills. That season, only two teams attempted 25 or more from deep and seven made at least 37 per cent.

By the 2016-17 season, those teams increased to 19 and 11. Last season, 30 and 13.

How far can Curry push the limits of imagination? Curry is 33 and this might be his finest season as a shooter, which sounds blasphemous given he owns a pair of MVPs and a slew of shooting records.

This reality, though, fortifies the idea of Curry staying on pace to make 4,000 from deep, given he signed a four-year extension this offseason. That would put the record into another ozone.

“Who knows?” Steph says. “I can tell you it’s way harder to stay at this level than to get here. There’s a beauty and ignorance in what it takes to get here. You don’t know how to do it until you do it. And then, when you do, you have to keep investing the effort, attention to detail, the work you put in, and the competition coming at you (because) they treat you differently. Draymond (Green) says he gets nervous before every camp because you have to do it all over again. I feel the same way.

“I get insecurity like, I know I’m good and I’ve done a lot of great things and I continue to push the envelope, but when you come into the season you have to do that over and over again. I got a lot of years left so I don’t know what the final 3-point number will be. It’s going to take a lot for somebody to do it but it’s not out of the question.”

There are many others who insist it is very much out of the question.

Dell Curry added: “First of all, he’s breaking his own records because he’s the only one who can do it. I can’t see anybody getting them. There will never be another 5-foot-3 point guard like Muggsy Bogues and I don’t think there will be another Steph. Remember, he’s got more years to push that record. And shooting’s the last thing to go.

“He’ll still be able to shoot even when the rest of his skills start to fade. I also don’t know of another player who’ll have the green light that Steph gets and takes the shots he does at various times in a game. I can’t see it. No way. And this is from a fan, not a father.”

Stephen Curry made the NBA’s 75th Anniversary Team, won three titles, has now claimed the Holy Grail of shooting records, became one of the biggest entertainers in basketball, changed the way it was played, is discussed in legacy terms and… isn’t done yet. He insists he has more to accomplish and nothing to prove.

“It’s not about anything in terms of how people look at me as a basketball player or where I’m ranked on all-time lists,” he says. “I feel I have the respect of my peers and continue to double down on that. I’m very confident in my career, what I’ve done, who I got to do it with. The accomplishment part was the fun part. And it continues to be.”

Credit: Sky Sports